Trump Tower – Alfa Bank

…No, it wasn’t spam marketing. “Publicly available internet records show that address, which was registered to the Trump Organization, points to an IP address that lives on an otherwise dull machine operated by a company in the tiny rural town of Lititz, Pennsylvania. From May 4 until September 23, the Russian bank looked up the address to this Trump corporate server 2,820 times — more lookups than the Trump server received from any other source. As noted, Alfa Bank alone represents 80% of the lookups, according to these leaked internet records.

Far back in second place, with 714 such lookups, was a company called Spectrum Health. Spectrum is a medical facility chain led by Dick DeVos, the husband of Betsy DeVos, who was appointed by Trump as U.S. education secretary. Together, Alfa and Spectrum accounted for 99% of the lookups.”CNN

Was a Trump Server Communicating With Russia? This spring, a group of computer scientists set out to determine whether hackers were interfering with the Trump campaign. They found something they weren’t expecting. By Franklin Foer Slate October 31, 2016 “In late spring, this community of malware hunters placed itself in a high state of alarm. Word arrived that Russian hackers had infiltrated the servers of the Democratic National Committee, an attack persuasively detailed by the respected cybersecurity firm CrowdStrike…Some of the most trusted DNS specialists—an elite group of malware hunters, who work for private contractors—have access to nearly comprehensive logs of communication between servers…

In late July, one of these scientists—who asked to be referred to as Tea Leaves, a pseudonym that would protect his relationship with the networks and banks that employ him to sift their data—found what looked like malware emanating from Russia. The destination domain had Trump in its name, which of course attracted Tea Leaves’ attention. But his discovery of the data was pure happenstance—a surprising needle in a large haystack of DNS lookups on his screen. “I have an outlier here that connects to Russia in a strange way,” he wrote in his notes. He couldn’t quite figure it out at first. But what he saw was a bank in Moscow that kept irregularly pinging a server registered to the Trump Organization on Fifth Avenue.

More data was needed, so he began carefully keeping logs of the Trump server’s DNS activity. As he collected the logs, he would circulate them in periodic batches to colleagues in the cybersecurity world. Six of them began scrutinizing them for clues.

(I communicated extensively with Tea Leaves and two of his closest collaborators, who also spoke with me on the condition of anonymity, since they work for firms trusted by corporations and law enforcement to analyze sensitive data. They persuasively demonstrated some of their analytical methods to me—and showed me two white papers, which they had circulated so that colleagues could check their analysis. I also spoke with academics who vouched for Tea Leaves’ integrity and his unusual access to information. “This is someone I know well and is very well-known in the networking community,” said Camp. “When they say something about DNS, you believe them. This person has technical authority and access to data.”)

The researchers quickly dismissed their initial fear that the logs represented a malware attack. The communication wasn’t the work of bots. The irregular pattern of server lookups actually resembled the pattern of human conversation—conversations that began during office hours in New York and continued during office hours in Moscow. It dawned on the researchers that this wasn’t an attack, but a sustained relationship between a server registered to the Trump Organization and two servers registered to an entity called Alfa Bank.

The researchers had initially stumbled in their diagnosis because of the odd configuration of Trump’s server. “I’ve never seen a server set up like that,” says Christopher Davis, who runs the cybersecurity firm HYAS InfoSec Inc. and won a FBI Director Award for Excellence for his work tracking down the authors of one of the world’s nastiest botnet attacks. “It looked weird, and it didn’t pass the sniff test.” The server was first registered to Trump’s business in 2009 and was set up to run consumer marketing campaigns. It had a history of sending mass emails on behalf of Trump-branded properties and products. Researchers were ultimately convinced that the server indeed belonged to Trump. (Click here to see the server’s registration record.) But now this capacious server handled a strangely small load of traffic, such a small load that it would be hard for a company to justify the expense and trouble it would take to maintain it. “I get more mail in a day than the server handled,” Davis says. “I’ve never seen a server set up like that.”

That wasn’t the only oddity. When the researchers pinged the server, they received error messages. They concluded that the server was set to accept only incoming communication from a very small handful of IP addresses. A small portion of the logs showed communication with a server belonging to Michigan-based Spectrum Health. (The company said in a statement: “Spectrum Health does not have a relationship with Alfa Bank or any of the Trump organizations. We have concluded a rigorous investigation with both our internal IT security specialists and expert cyber security firms. Our experts have conducted a detailed analysis of the alleged internet traffic and did not find any evidence that it included any actual communications (no emails, chat, text, etc.) between Spectrum Health and Alfa Bank or any of the Trump organizations. While we did find a small number of incoming spam marketing emails, they originated from a digital marketing company, Cendyn, advertising Trump Hotels.”)

Spectrum accounted for a relatively trivial portion of the traffic. Eighty-seven percent of the DNS lookups involved the two Alfa Bank servers. “It’s pretty clear that it’s not an open mail server,” Camp told me. “These organizations are communicating in a way designed to block other people out.”

Earlier this month, the group of computer scientists passed the logs to Paul Vixie. In the world of DNS experts, there’s no higher authority. Vixie wrote central strands of the DNS code that makes the internet work. After studying the logs, he concluded, “The parties were communicating in a secretive fashion. The operative word is secretive. This is more akin to what criminal syndicates do if they are putting together a project.” Put differently, the logs suggested that Trump and Alfa had configured something like a digital hotline connecting the two entities, shutting out the rest of the world, and designed to obscure its own existence. Over the summer, the scientists observed the communications trail from a distance.” Slate

Trump’s Server, Revisited

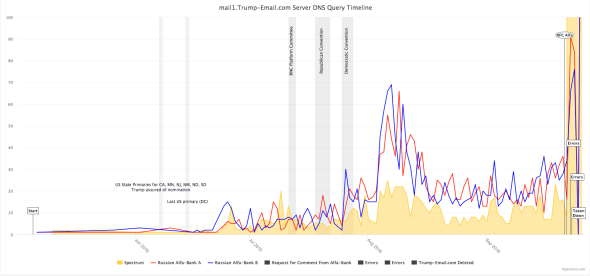

Sorting through the new evidence, and competing theories, about the Trump server that appeared to be communicating with a Russian bank. By Franklin Foer Slate November 2, 2016 “In a detailed post critiquing my piece, cybersecurity expert Rob Graham wrote, “The evidence available on the Internet is that Trump neither (directly) controls the domain trump-email.com, nor has access to the server.” This echoes the point raised by Vox, the Intercept, and others that the server was not operated by the Trump Organization directly. Rather, it was run and managed by Cendyn, a vendor that organizes email marketing campaigns for hotels and resorts…I entered the internet protocal address for mail1.trump-email.com to check if it ever showed up in Spamhaus and DNSBL.info. There were no traces of the IP address ever delivering spam…There’s a much smaller spike during the Democratic convention and no apparent increase before or during the Republican convention,” he noted. “In short, this chart seems to be totally unrelated to the political calendar.” He wonders why the largest spike occurs in August, after the party conventions. This happened to be a moment of potential interest in Russia, since those weeks were the denouement of the Paul Manafort era in the Trump campaign, with the exposure of logs showing he received $12.7 million in off-the-book payments from the Putin-backed Party of Regions. But Lee’s fundamental response is understandable: The chart shows possible correlations, not proven causation. There were reports that the Trump campaign had ordered the Republican Party to rewrite its platform position on Ukraine, maneuvering the GOP toward a policy preferred by Russia, though the Trump campaign denied having a hand in the change. Then Trump announced in an interview with the New York Times his unwillingness to spring to the defense of NATO allies in the face of a Russian invasion. Trump even invited Russian hackers to go hunting for Clinton’s emails, then passed the comment off as a joke. (I wrote about Trump’s relationship with Russia in early July.) After Tea Leaves posted his analysis on Reddit, a security blogger who goes by Krypt3ia expressed initial doubts—but his analysis was tarnished by several incorrect assumptions, and as he examined the matter, his skepticism of Tea Leaves softened somewhat. I asked nine computer scientists—some who agreed to speak on the record, some who asked for anonymity—if the DNS logs that Tea Leaves and his collaborators discovered could be forged or manipulated. They considered it nearly impossible.

Alfa Bank emerged in the messy post-Soviet scramble to create a private Russian economy. Its founder was a Ukrainian called Mikhail Fridman. He erected his empire in a frenetic rush—in a matter of years, he rose from operating a window washing company to the purchase of the Bolshevik Biscuit Factory to the co-founding of his bank with some friends from university. Fridman could be charmingly open when describing this era. In 2003, he told the Financial Times, “Of course we benefitted from events in the country over the past 10 years. Of course we understand that the distribution of state property was not very objective. … I don’t want to lie and play this game. To say one can be completely clean and transparent is not realistic.”

To build out the bank, Fridman recruited a skilled economist and shrewd operator called Pyotr Aven. In the early ’90s, Aven worked with Vladimir Putin in the St. Petersburg government—and according to several accounts, helped Putin wiggle out of accusations of corruption that might have derailed his ascent. (Karen Dawisha recounts this history in her book Putin’s Kleptocracy.) Over time, Alfa built one of the world’s most lucrative enterprises. Fridman became the second richest man in Russia, valued by Forbes at $15.3 billion.

Alfa’s oligarchs occupied an unusual position in Putin’s firmament. They were insiders but not in the closest ring of power. “It’s like they were his judo pals,” one former U.S. government official who knows Fridman told me. “They were always worried about where they stood in the pecking order and always feared expropriation.” Fridman and Aven, however, are adept at staying close to power. As the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia once ruled, in the course of dismissing a libel suit the bankers filed, “Aven and Fridman have assumed an unforeseen level of prominence and influence in the economic and political affairs of their nation.”

Unlike other Russian firms, Alfa has operated smoothly and effortlessly in the West. It has never been slapped with sanctions. Fridman and Aven have cultivated a reputation as beneficent philanthropists. They endowed a prestigious fellowship. The Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, the American-government funded think tank, gave Aven its award for “Corporate Citizenship” in 2015. To protect its interests in Washington, Alfa hired as its lobbyist former Reagan administration official Ed Rogers. Richard Burt, who helped Trump write the speech in which he first laid out his foreign policy, previously served on Alfa’s senior advisory board.* The branding campaign has worked well. During the first Obama term, Fridman and Aven met with officials in the White House on two occasions, according to visitor logs.

Fridman and Aven have significant business interests to promote in the West. One of their holding companies, LetterOne, has vowed to invest as much as $3 billion in U.S. health care. This year, it sank $200 million into Uber. This is, of course, money that might otherwise be invested in Russia. According to a former U.S. official, Putin tolerates this condition because Alfa advances Russian interests. It promotes itself as an avatar of Russian prowess. “It’s our moral duty to become a global player, to prove a Russian can transform into an international businessman,” Fridman told the Financial Times.

* * *

Tea Leaves and his colleagues plotted the data from the logs on a timeline. What it illustrated was suggestive: The conversation between the Trump and Alfa servers appeared to follow the contours of political happenings in the United States. “At election-related moments, the traffic peaked,” according to Camp. There were considerably more DNS lookups, for instance, during the two conventions.

In September, the scientists tried to get the public to pay attention to their data. One of them posted a link to the logs in a Reddit thread. Around the same time, the New York Times’ Eric Lichtblau and Steven Lee Myers began chasing the story.* (They are still pursuing it.) Lichtblau met with a Washington representative of Alfa Bank on Sept. 21, and the bank denied having any connection to Trump. (Lichtblau told me that Times policy prevents him from commenting on his reporting.)

The Times hadn’t yet been in touch with the Trump campaign—Lichtblau spoke with the campaign a week later—but shortly after it reached out to Alfa, the Trump domain name in question seemed to suddenly stop working…Four days later, on Sept. 27, the Trump Organization created a new host name, trump1.contact-client.com, which enabled communication to the very same server via a different route. When a new host name is created, the first communication with it is never random. To reach the server after the resetting of the host name, the sender of the first inbound mail has to first learn of the name somehow. It’s simply impossible to randomly reach a renamed server. “That party had to have some kind of outbound message through SMS, phone, or some noninternet channel they used to communicate [the new configuration],” Paul Vixie told me. The first attempt to look up the revised host name came from Alfa Bank.“

Eric Lichtblau, an investigative reporter following the money and who broke the story on October 31, 2016, met with Alfa Bank on September 21, 2016, and wrote “Investigating Donald Trump, F.B.I. Sees No Clear Link to Russia” on October 31, 2016. He “became the Assistant Managing Editor at CNN’s Washington Bureau.” WaPo on April 10, 2016, and by July 3, was fired. “Lichtblau was a key reporter in a multiple-byline story alleging that Comey would refute a Trump allegation during his then-upcoming Senate testimony. The story was wrong.” Washington Post

The spike in August was at the same time the Mercer camp and their SuperPac money publicly joined Trump, with Kellyanne Conway replacing Paul Manafort as Campaign Director and Steve Bannon getting more heavily involved in the Campaign.

“His server behavior alarmed one computer expert who had privileged access to this technical information last year. That person, who remains anonymous and goes by the moniker “Tea Leaves,” obtained this information from internet traffic meant to remain private. It is unclear where Tea Leaves worked or how Tea Leaves obtained access to the information. Tea Leaves gave that data to a small band of computer scientists who joined forces to examine it, several members of that group told CNN, which has also reviewed the data…Alfa Bank has maintained that the most likely explanation is that the server communication was the result of spam marketing…Alfa Bank said it used antispam software from Trend Micro, whose tools would do a DNS lookup to know the source of the spam…Alfa Bank said it brought U.S. cybersecurity firm Mandiant to Moscow to investigate. Mandiant had a “working hypothesis” that the activity was “caused by email marketing/spam” on the Trump server’s end, according to representatives for Alfa Bank and Mandiant. The private investigation is now over, Alfa Bank said. Cendyn is the contractor that once operated marketing software on that Trump email domain…But Cendyn acknowledged that the last marketing email it delivered for Trump’s corporation was sent in March 2016, “well before the date range in question”…Cendyn claims the Trump Hotel Collection ditched Cendyn and went with another email marketing company, the German firm Serenata, in March 2016. Cendyn said it “transferred back to” Trump’s company the mail1.trump-email.com domain…Serenata this week told CNN it was indeed hired by Trump Hotels, but it “never has operated or made use of” the domain in question: mail1.trump-email.com…Upon hearing that Cendyn gave up control of the Trump email domain, Camp, said: “That does not make any sense to me at all. The more confusing this is, the more I think we need an investigation.” Other computer experts said there could be additional lookups that weren’t captured by the original leak. That could mean that Alfa’s presence isn’t as dominant as it seems. But Dyn, which has a major presence on the internet’s domain name system, spotted only two such lookups — from the Netherlands on August 15. Alfa Bank insists that it has no connections to Trump. In a statement to CNN, Alfa Bank said neither it, bank cofounder Mikhail Fridman and bank president Petr Aven “have had any contact with Mr. Trump or his organizations.” CNN